What if, on 911, first responders had just walked on by… did they choose who they would help? Did they even ask? At what point did a first responder decide, “Ah, nah!” and walk on by?

God’s heart for mercy: our own hearts being transformed by God’s merciful kindness, we are created (in Jesus) for obedience to Him - to do the good works that are the fruit of that transformed heart, having been transformed, is intended then to express mercy - being a recipient and beneficiary of God’s mercy.

Luke 10:25-37 the Good Samaritan: the kingdom of heaven’s first responder

Do I ask the same question? Who is my neighbor? To whom and for whom am I responsible? To whom can or should I render aid? To whom should I not? And, if the scribe as asking this in an attempt to justify himself, what must the people have been thinking and waiting to here? And are there times and circumstances, and people in those circumstances, where I might try to justify my response?

Jesus’ Jewish audience would have been spellbound, on the edge of their seat, waiting to see how this story would unfold and end. Each detail would have peeked their imagination - proking emotions, thoughts, and judgments as the circumstances unfolded and each character is introduced.

The scribe - one learned in the Law, an expert in the Tora, the “Five Books of Moses”. Probably a Pharisee - as the Pharisee (and not a Saducee) would have believed in the resurrection of the dead and eternal life, and, they were scrupulous with regard to being “clean”, undefiled by anything “impure” - including other people. So, they were committed to knowing who their “neighbor” was and would keep separate, and even judge, anyone who wasn’t clean - thus, not their neighbor - refusing to associate with anyone who was not as “rightesous” as they were. It was among themselves, Pharisees and their associates, that they would consider “neighors”. This scribe was attempting to exalt his own sense of (self) righteousness and justify his practive.

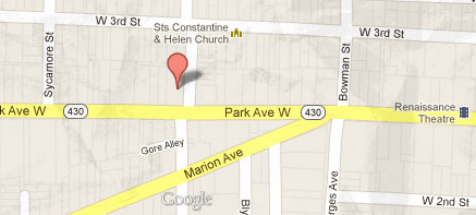

The place and the journey - this journey, and road in particular, was notoriously difficult and dangerous - even in modern times, people are warned of its inherent perilous ways. Anyone seen traveling alone on this road, especially with goods or anything of value would have been considered a fool who got was coming to them.

The traveler - the foolish man who had little sense who would now be seen with scorn and ridicule… Jesus is setting us up.

What might the listening Jew (and maybe even the hidden Samaritan) have been thinking as each character is revealed? How would who act? Would they first think “Ah, a priest, he’ll render aid!”, but alas, he walks by, and that, on the other side… “Well, that makes sense, he cannot defile himself, he has to remain “clean” (Numbers 19:11), and besides, does this man not deserve what he got?!”

The Priest - The priests of Israel were a group of qualified men from within the tribe of the Levites who had responsibility over aspects of tabernacle or temple worship.

The Levite - but not a Priest - often a lay leader or servant of the local body, one who would exemplify all things “Christian”.

A little more study: https://www.gotquestions.org/difference-priests-Levites.html )

If we were to write this story today, who might we pick as the…

Traveler - fool-hearty, unwise, deserving of the beating he took

Priest, who was Levite - a qualitified vocational and professional religious teacher and representative between God and man - what of mercy, grace, and charity?

Levite, Samaritan - the despised, and in many ways, a historical, sworn enemy, one with a lineage of antagonism and mutual dislike or even hatred.

Samaritan: Jesus mercy in using this parable to convict the Jews of their sin.

Who were the Samaritans?

The growing divide between the Samaritans and the Jews is not explicitly chronicled in a single narrative in the Scriptures. However, there are several passages that provide insights into the historical and cultural context, as well as the strained relationship between these two groups:

1. 2 Kings 17:24-41: This passage describes the origins of the Samaritans after the Assyrian conquest of the northern kingdom of Israel. The Samaritans were brought into the region and introduced their own religious practices, resulting in a mixture of Israelite and pagan beliefs. This sets the stage for the later tensions and divisions between Samaritans and Jews.

2. Ezra 4:1-5: This passage mentions opposition and conflict faced by the Jews in rebuilding the Temple in Jerusalem during the time of Cyrus the Great. It includes references to Samaritans who offered assistance but were rejected due to their perceived impure lineage. This rejection further deepened the divide between the two groups.

3. Nehemiah 4:1-3: In this section, when Nehemiah and the Jews were rebuilding the walls of Jerusalem, they faced opposition from Samaritans who ridiculed and mocked their efforts. This highlights the hostilities and conflicts between the two communities.

4. John 4:1-42: This narrative recounts Jesus' encounter with the Samaritan woman at the well. It reflects the social, ethnic, and religious tensions between Jews and Samaritans. Jesus' interaction with the woman and his message of inclusivity challenge the prevailing animosity between the two groups.

While these passages shed light on the historical background and strained relationship between Jews and Samaritans, it's important to remember that they provide glimpses rather than a comprehensive account. The ongoing division and animosity between the two groups were the result of a complex historical process, religious differences, and cultural tensions.

Do we think the Samaritan didn’t know what the Jews thought of him? Or, even, what he might of thought of or felt the Jews?

Did the animosity between the Jew and the Samaritan just go one way?

The animosity and contempt between the Samaritans and Jews during Jesus' time were not one-sided but reciprocal. Both groups held negative attitudes towards each other, reflecting a deep-seated mutual disdain. While it is challenging to quantify or generalize the attitudes of every individual Samaritan or Jew, historical and biblical records suggest a reciprocal hostility between the two groups. Here are some factors that contributed to the mutual contempt:

1. Historical Conflicts: The historical conflicts between the Samaritans and Jews, including the defilement of the Jerusalem Temple by Samaritans during the time of Nehemiah, created a lasting bitterness between the two groups. These historical events fueled animosity and contributed to the mutual contempt.

2. Religious Rivalry: The religious differences between Samaritans and Jews intensified their mutual disdain. The Samaritans had their own distinct religious practices centered around Mount Gerizim, while the Jews emphasized worship at the Jerusalem Temple. Each group considered the other's religious practices to be impure or false, contributing to a deep-seated contempt.

3. Cultural and Ethnic Divisions: The Samaritans were considered a mixed population, resulting from intermarriage between the remnants of the northern kingdom of Israel and non-Israelite groups. The Jews viewed themselves as the true descendants of Abraham and held a sense of ethnic pride and superiority. These cultural and ethnic divisions reinforced mutual contempt and prejudice.

4. Social Stigma and Discrimination: Both Samaritans and Jews experienced social stigma and discrimination from each other. The Samaritans were seen as impure and held in low regard by the Jews, while the Samaritans likely held negative views of Jews due to their exclusionary attitudes.

While it is important to acknowledge that not all Samaritans or Jews harbored contemptuous attitudes, the prevailing sentiment among many individuals in both groups reflected mutual animosity and contempt. Jesus' choice to present a Samaritan as the hero of the Parable of the Good Samaritan was a deliberate attempt to challenge and overcome these deeply entrenched biases and promote reconciliation and love between the two groups.

To the holders of “righteousness” this story would have been utterly offensive and contrary - Jesus would be calling them out for a myriad of sins that were contrary to:

God’s intended purpose for Israel as a light to the nations and an example of His grace and love.

Misrepresenting God’s heart for the nations - and this by “God’s people”.

The origins and maturing of the attitudes toward non-Jews in the Bible can be traced through various passages that reflect the evolving perspectives and experiences of the Israelites. Some key sections that shed light on this development include:

1. Old Testament Origins:

- Genesis 12:1-3: God's covenant with Abraham marks the beginning of God's plan to bless all nations through the descendants of Abraham.

- Exodus 19:5-6: God calls the Israelites a "treasured possession" and a "kingdom of priests," suggesting their role as intermediaries between God and the nations.

2. Mosaic Law and Israel's Identity:

- Leviticus 19:34: The command to love the stranger or foreigner as oneself reflects an early recognition of the need for kindness and inclusion of non-Israelites within their community.

- Deuteronomy 7:1-6: In these passages, the Israelites are instructed to utterly destroy the Canaanite nations as they enter the Promised Land. This reflects a period of distinct separation and exclusion as part of the conquest of the land.

3. Prophetic Voices and Expanding Perspectives:

- Isaiah 42:1-4; Isaiah 49:6: These passages depict the servant of the Lord (often associated with the Messiah) being a light to the nations, pointing to a broader redemptive purpose for Israel beyond their own borders.

- Jonah: The book of Jonah highlights God's concern for all nations, as Jonah is sent to proclaim God's message of repentance to the people of Nineveh, who were not Israelites.

4. New Testament Fulfillment:

- Matthew 28:18-20: The Great Commission commands the disciples to make disciples of all nations, emphasizing the universal scope of the gospel.

- Acts 10:9-48: The conversion of Cornelius, a Gentile centurion, and Peter's realization that God shows no partiality, marks a significant shift in perspective towards non-Jews in early Christianity.

These passages, among others, demonstrate the progression of attitudes and perspectives towards non-Jews in the Bible. While there were periods of separation and exclusivity, there were also glimpses of God's broader redemptive plan for all nations. Jesus Christ and the early Christian movement ultimately expanded the understanding of God's love and salvation to include all people, transcending ethnic boundaries and providing a foundation for a more inclusive approach.

And a call to repentance to live a life of true righteousness as expressed by a heart itself transformed by God’s mercy upon it - a concept having been long lost on them. (I have not come to the healthy and the righteous, but to the sick and simmer; not the “wise and the learned, but “little children” - thus we are called to be in view of God’s mercy, and be merciful just as He is merciful… having ourselves have been comforted by God’s love, we now bring comfort)

Mercy rendered, is the gospel of truth To whom am I to be kind, and again, to what end? What are my intentions? What are the intentions of God’s kindness toward us? Do we believe God at His word?

Each one of us, having people in our own lives, to whom God has sent us, will see them through our own lens - our thinking, feeling, experiences, and perspectives., and these thoughts and feelings will usually be relative to our own person, what appeals to us and what doesn’t, what is this we are or are not - we will see it we see it - not always like someone else might, or feel how it is we might feel about it versus have someone else meeting abou

To whom am I to render mercy? And to what end?

Believers:

Encouragement

Admonition (reminders of the truth of the gospel of grace for salvation and acceptance)

Loving and gentle correction, discipline, and restoration

Mercy - extended with insight and love - a deep desire for thier well-being, God’s best

Who are the brothers and sisters in my life am I called to be merciful?

Unbelievers:

We are to be examples of God’s grace - as (ourselves being) recipients of unmerited favor

Looking past their being a “sinner” or an enemy, to their being one of God’s valued making and image bearer, for whom Christ came, also

Render aid when and where possible regardless of my feelings about them and maybe have my feelings change - because they valued by God (as in grief for their condition, deeper compassion, hope for their wellbeing AND God’s best for them - which would be what?),

Being prepared to give a reason for our hope when asked because they see and experience something different with me - a righteousness that is the reflection of Jesus - who came to me and treated me, in spite of me, as a, His, neighbor.

First responders are committed to rendering aid regardless of the object or subject, do we see ourselves is the first responders looking about having the last of the dying? My brothers and sister, struggling in sin?

Can we, will we see Thor plight and respond I. Kind?

For the next few weeks we will looking into what we need to be to be the first responders Fox had made us to be